Gone to the Beach

by Max Blue

I still feel desolate.

We arrive at LAX on a small plane from San Francisco. I get the impression that ours is one of the only flights that isn’t chartered or private.

Looks like it’s going to rain, Amy says, doing the peering position with head and neck, shoulders back, as she slides up the little plastic window cover.

Amy makes observations, professionally. She has taken the week off from her work analyzing data to come with me to the art fair, in a strictly romantic capacity. For her, this is a free vacation. She can’t help but do the numbers.

The plane is too small to have screens on the seats in front of us, no way to check the weather forecast.

It won’t rain, I say. They wouldn’t have scheduled the fair for a week when it was going to rain.

They schedule these things years in advance, Amy says.

We walk off with carry-ons. The sky is overcast but the tarmac is hot. The airport is crawling with Art People. They carry flat files and toll complicated stacks of luggage: art fair booths collapsed into a few boxes. They have pedantic styles of dress.

Getting a cab to Venice is miserable. We end up sharing with a man who seems concerned by the fact that we don’t know who he is. He has a lanyard around his neck. I make a point of asking him his name. All he tells us is that he is affiliated with some Paris gallery, though his accent is Swedish.

When I mention this to Amy, after we are let out in front of the hotel, she says, Europe is a multicultural fuckfest.

The hotel is actually on the beach. Our room has glass doors that open over sand. As far as descriptions go, cabana comes to mind.

Maybe they made a mistake, I say when we get inside the room.

(Mistake or no, I’m glad because I feel that the quality of the room legitimizes me: Amy now has some material referent for my success; art critic equals beachfront cabana.)

I don’t think it’s a mistake, Amy says. The nice rooms have their own jacuzzies.

*

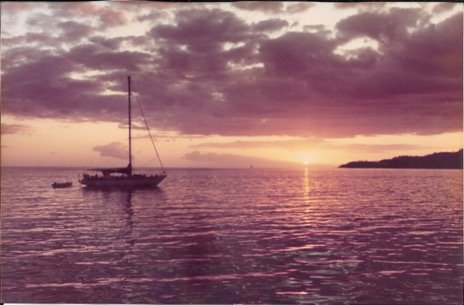

Our first night here, after an early dinner somewhere along the boardwalk, I leave Amy reading in bed and walk down from the hotel to the stretch of beach where the fair is being set up. There are chalk markings on the ground, outlining the idea of the fair (though, in retrospect, this seems impossible: chalk on sand?). Groups of men in black tee shirts carry platforms piecemeal onto the beach, laying them out where the tents will be pitched. I wait and watch the first tent go up at sunset, pointed top in twilight.

I am not the only watcher on the sand: a large man in cargo shorts and a Hawaiian shirt stands a few feet away, clenching and unclenching his left hand.

Here for the fair? I ask.

No, he says. We just come every summer, the wife and I.

He lurches closer, ankles deep in the sand.

Every few years it seems like this is going on, he says. What, car show? Fair, you said?

Art fair, I say.

What sort of stuff? Little dots that make a bigger picture? Naked women?

Probably some of both, I say. Sculptures.

My son takes pictures. Photographs on hikes and things. Those I’ll hang. Those I like. Nice stuff to look at. What about you?

Journalist, I say. They pay me to come out and get a feel for the thing.

So, what, you like it? Or is it just a paycheck?

I’m not sure what to say. I like it and it’s a paycheck. But somehow, neither part of that equation seems exciting anymore.

Looks like it’s going to rain anyway, the man says.

Have you heard that?

Looks like it, he says.

What are they looking at, Amy and this man, in which they see rain? The clouds? Cloud patterns?

Cloud patterns? I ask.

Just the look of it, he says.

*

When I get back to the cabana, Amy is sleeping naked on top of the comforter.

I think, Naked pictures.

I leave the door of the cabana open to get a breeze going through the room, swirl the stifled air.

I lift the open book off her chest and stick a cocktail napkin in between the pages, set it down on the bedside table and lie down next to her, not bothering to undress. Up close in the dark, her body is tiny dots.

No agenda, I think.

I turn on the television and watch with the sound off, the ends of movies, one after the other.

Amy rolls over, asks about my walk without opening her eyes.

You take pictures on your phone, I say. Hikes and things. I don’t do this.

I don’t take hikes, Amy says, but I do take pictures on my phone. Dogs and lattes. True: you don’t do this.

What are the pictures for? I ask. What do those pictures mean?

What time is it?

A little after one.

Do you ever stop working?

I’m not working, I say, I’m thinking about what the pictures mean.

Well that’s pretty much the job description, isn’t it?

*

The next morning is mostly a matter of picking up my press pass, a process of waiting in a line with other journalists, trading shifty glances. After an hour or so, it’s my turn to see my name crossed off a list, to be handed a lanyard and a folder of press materials. The lanyard means carte blanche: get in anyone’s way; off to the races. I will attempt to visit all of the fifty-six galleries in the fair’s roster, and inevitably miss the mark.

Just inside the exhibition hall, I pass beneath a piece that has been hung outside a gallery near the entrance: it’s a white poster board sign with black hand lettering which reads, It’s All Going Very Well, No Problems at All. I take this as a sort of blessing.

The men must have worked through the night, because most of the tents are set up and galleries are starting to come in, beginning to block out their interior spaces. No work has been hung yet; the stark white temporary walls are still being rolled into position. A few ostensible sculptures are shrouded in packing foam, like strange mummified animals.

The smell is hyper-clean.

In the press tent (open sides, leather couches), they have a lunch service the quality of which is telling of how little the fair values the press. But no one is expected to write about the papery, plastic-wrapped sandwiches and mealy fruit cups.

I spend most of the afternoon bothering various gallerists and artists for quotes amidst the harried process of erecting their booths.

There are nervous men from France and Japan gnawing at new manicures, women ordering men hefting plastic-wrapped packages, artworks shrouded. People drilling holes and measuring and redrilling.

Lauren Hapsburg has brought dozens of polaroid snapshots of her star artist’s vagina. Matsumoto Yoshika has brought a selection of new works by a group of painters he represents and one he doesn’t. The young sculptor Ari Phelps has been given the entirety of the Statler Paris booth for a single, complex sculpture requiring several hours of assembly. I run into the British photographer Graham Sterling who insists on telling me how he wants to ejaculate inside a certain curator’s Tiszas. Jill Omandi has brought Lloyd Ali’s latest series of facsimile folk arts, masks and baskets, while Ali himself has stayed behind at his summer home in the Swiss Alps. There is a high pedestal toward the back of the main tent, about six feet tall and three feet thick. The pedestal can be seen from the entrance, all the way down the center aisle. No one knows what it’s for.

The tent is already beginning to empty out by dinnertime and once it’s clear that no one is going to make much more headway setting up that day, I go collect Amy at the hotel. We go for a walk through the town. There are bridges over canals and gondolas that go underneath them. Like much of America, this town is a facsimile, right down to the name.

Amy has been out most of the day, when not tanning by the pool (I would never lay out on the beach, she says), and points out things she made mental notes to show me. I forget all of them. She takes me to a place for dinner, where she made a reservation, earlier, between dress shops.

I think they raise the prices during these festivals, she says over scampi.

We spend the rest of the evening at the pool and in bed where the blue glow from the television makes the brown of Amy’s nipples look dark purple, almost black. Crash course in color theory: Lover’s Body by Blue Light.

I step outside the sliding door for a cigarette. When I come back in, Amy looks up.

You’re all wet, she says.

It’s starting to come down.

Shake off by the door. Didn’t I say?

Statistically, what were the chances?

Either zero or a hundred.

I’m not following, I say, unbuttoning my shirt.

Either it’s going to rain or it isn’t, Amy says. Zero or a hundred.

Well, I say, sliding the glass door shut, it’s raining.

*

The next morning is extremely tense. The rain has picked up in the night and is coming down in violent sheets. People hurry along the temporary boardwalk that connects the tents which now look a bit less festive—a bit more miserable—beneath the clouds. I join the crowd, covering my head with a newspaper since the hotel has already run out of umbrellas.

Members of the press are allowed inside an hour before the fair is officially open to the public. In the main exhibition hall, the big top, I’m surprised to find many booths still in the hurried process of mounting work, what I soon realize is actually a mad rush to remove pieces from the temporary walls, to cover them with tarpaulins and tablecloths.

The roof has started leaking.

It isn’t a heavy drip, but steady, in one spot at about the middle of the tent. It’s a long way from the peaked top to the makeshift floorboards, and the drops land with a distinct smack. A man from the catering company brings a bucket. Someone mentions that it is the second bucket of the morning, that the first one filled up in a little under an hour.

The story I manage to string together from harried onlookers: the leak started sometime after midnight, unnoticed by security. By the time the caterers started coming in around five in the morning, the puddle was significant. Men shoveled water. The first bucket was placed. Richard Santos and his gallery assistant were the first to start tearing down their booth.

By the time I had gathered as much information, three more leaks had begun dripping in different areas of the tent.

Most of the gallery people seem to have abandoned their efforts, two hundred bodies gathered in more or less stasis.

It’s getting bigger, someone says.

More heavy, someone else.

Heavier, another voice corrects.

More persistent, an even-toned woman says.

It’s a bloody waterfall, Graham Sterling says in my ear.

With a horrendous sound somewhere between tearing and crashing, the midsection of the ceiling splits open like a scalpelled stomach and a torrent of water pours down on all of us.

As far as descriptions go, pandemonium comes to mind. Panic sets in frenetically. Getting quotes becomes difficult.

Everyone is dashing, some slipping in flat-soled dress shoes, others carrying their high heels, running barefoot or pantyhosed, women screaming, men screaming, a crush to toss coats and jackets over works of art caught beneath the downpour, the sound of millions of dollars washed away. I feel a little juvenile holding out my recording device at passersby. Mostly I just get expletives.

Security guards arrive en masse and begin herding us toward the exit. Safety precautions are cited; crying curators are torn away from their investments.

On my way out of the exhibition hall, soaking wet, I spot the sign I had noticed the day before, hanging near the entrance. Only now, I see that the reverse side carries a very different message: It’s Going Very Badly, It’s A Terrible Disaster.

You never know when things will fall apart.

*

The sand has turned to mud. The air is actually warm. The day seems trapped in twilight. The rain has stopped.

By the time I get back to the cabana, it’s only slightly past nine o’clock. I expect to find Amy still asleep, or staring at the television with room service balanced on her thighs. But Amy isn’t there. There’s a cocktail napkin on the bedspread, with something written on it in her quick, cursive hand. I pick it up and read the note.

Gone to the beach.

Max Blue is a writer living in San Francisco. His criticism and reporting have appeared in Cultured and Hyperallergic, among others, and he is a regular contributor to the San Francisco Examiner. His short fiction has appeared in Mount Hope and Your Impossible Voice, among others. He holds a degree in the History and Theory of Contemporary Art from the San Francisco Art Institute and an MFA in Writing from the University of San Francisco. More can be found at maxbluewriter.com.